If you want to become a stronger rider next season, you may consider including some high intensity (HIT) intervals in your off-season break.

There is compelling evidence to suggest that your level of maintenance training during off-season dictates your development next year.

High intensity training maintains performance during off-season

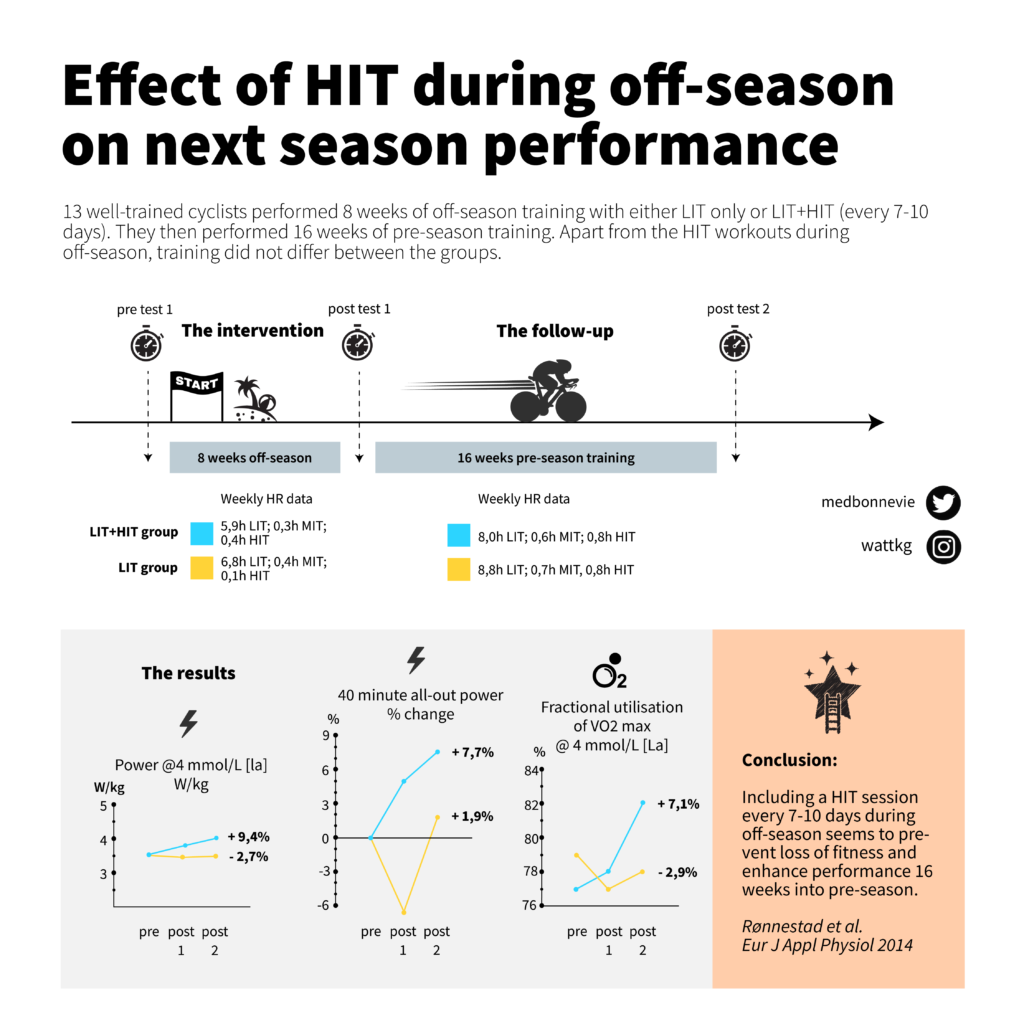

In a study from 2014, Rønnestad and colleagues compared the effects of two different training regimes during off-season on performance the following pre-season (1).

One group of riders conduct low intensity training only during the 8 week off-season period. Whereas a second group performed low intensity training combined with regular high intensity intervals in the same period.

The HIT workout was performed every 7-10 days and consisted of 5 x 6 minutes or 6 x 5 minutes high intensity work.

After the 8 weeks of off-season, both groups performed 16 weeks of regular pre-season training. At this stage, riders were free to perform their preferred training.

Both groups were tested before off-season, after off season (week 8) and after pre-season (week 24). 13 well-trained cyclists partook in the experiment (means: age 30-32 years, VO2 max 68-69 ml/L/min).

What did they find?

Before off-season, there were no differences between the cyclist groups with regards to VO2 max, Wmax, power at 4 mmol/L lactate, fractional utilisation of VO2 max, power at 40-minute all-out or body mass.

During the off-season period the HIT+LIT group reduced their training volume from 10.3 to 6.7 hours per week. The LIT group displayed a similar volume reduction from 10.6 to 7.3 hours per week.

The first few differences in results appeared after 8 weeks of off-season. Here, the HIT+LIT group had improved in two parameters compared to the LIT group:

- power at 4 mmol/L lactate (+5.4% vs -4.7%)

- power during 40-min all-out (+5.1% vs -6.4%)

A further 16 weeks into pre-season training, an interesting observation was made – the HIT+LIT group maintained their physiological “head start” from week 8. Despite similar pre-season training, the LIT group was unable to catch up on ground lost during off-season.

By week 24, following 16 weeks of pre-season training, the HIT+LIT group was still ahead in several fitness parameters. The changes given below refer to difference between baseline and week 24 (for LIT+HIT and LIT groups, respectively):

- power at 4 mmol/L lactate (+9.4% vs -2.7%)

- fractional utilisation of VO2 max at 4 mmol/L [La] (+7.1% vs -2.9%)

- power during 40-min all-out (+7.7% vs + 1.9%)

Additionally, there were no significant differences between the groups in W max, body mass or VO2 max after off-season or pre-season training.

In summary, the cyclists who did low intensity training only appeared to lose performance during off-season. And strikingly, they struggled to develop beyond their baseline test levels with 16 weeks of pre-season training.

In contrast, the cyclists who combined low and high intensity training appeared to counteract de-training during off-season. These riders arrived at the end of pre-season training with a considerably higher performance level than the LIT group did.

What do we make of these results and how do they matter to your off-season training?

Caveats

There are a few aspects of this study worthy of further scrutiny.

On the positive side, the authors monitored training data prior to and after the experimental off-season period. Their data show that training in the two groups were the same both before off-season, as well as during the subsequent pre-season training.

This means we are comparing apples with apples. As opposed to comparing apples and oranges. As far the authors could control, the only difference between the groups was the HIT training during off-season. Furthermore, there was no difference in training load between groups during off-season. So we can likely attribute the difference in results to the type of stimulus (HIT vs. LIT), as opposed to one group training more than the other.

There were no differences between groups in total training load during the transition period, pointing towards the importance of incorporating HIT in the training schedule for well-trained athletes.

– Rønnestad et al. Eur J Appl Physiol 2014

Keen eyes may have spotted that the HIT+LIT group not only counteracted fitness loss during off-season. They actually improved in some parameters (+5% W @ 4 mmol/L and +5% W during 40-min all-out).

This is perhaps somewhat unexpected during a period that saw a 40% reduction in training load. That being said, a 40% reduction in training load is well-within recommended parameters for tapers during peaking protocols. So perhaps the HIT+LIT group essentially performed an effective (though unusually long) taper? Alternatively, we cannot entirely rule out that results have been influenced by factors outside of the control of the scientists.

Furthermore, there are a few more aspects of this study design to be aware of when interpreting the results.

For starters, the sample size of 13 participants is a rather small number. Again, a small sample size increases the risk of results being influenced by factors that the scientists do not control.

Furthermore, the authors state that riders were allowed to decide which of the two off-season strategies they wanted to perform. Typically, scientists desire to randomise participants into either group. This helps prevent a skewed selection of characteristics in any group (if there are both apples and oranges in your pool of athletes, randomisation helps spread them evenly in both groups). However, randomisation was not achieved in this study.

Further evidence in support of off-season intensity work

With the above limitations in mind, the question remains how you should conduct your off-season in order to set yourself up for the best possible development the coming season.

For starters, this is not the only study to highlight the impact of off-season training on future development.

Back in 1995, Mujika and colleagues examined the variations in performance among 18 elite swimmers (2). They compared athletes who improved their personal record of previous year with athletes who did not improve. Similar to the results of Rønnestad et al, they found that improving athletes displayed a lower degree of fitness loss during off-season. In contrast, athletes who did not improve experienced a greater degree of de-training in off-season.

In more recent years, Taylor & Almquist et al examined the use of intensity work during off-season (3). They included repetitions of 30 second all-out sprints in low intensity rides during a 3 week off-season period. Like Rønnestad et al, they then measured performance upon start of pre-season training and further 6 weeks into pre-season.

They too found that riders who performed LIT rides with sprints during off-season showed stronger performance 6 weeks into pre-season training compared to riders who did traditional LIT rides only in off-season.

Again, adding use of (high) intensity during off-season seemed to benefit riders well into pre-season training.

I have discussed the findings on sprints in low intensity rides further here.

Should you do HIT during off-season?

The results on off-season intensity work are indeed compelling.

However, you should also keep in mind that off-season represents an opportunity for mental and physical recovery. There is little use in maintaining capacity during off-season if you burn out from lacking motivation during the following season.

Therefore, you will need to balance your personal need for time off cycling with trying to mitigate the effects of de-training. However, I am hoping that this article has provided some food for thought on how to optimise your off-season. So that you may give yourself a greater chance for strong development in the upcoming season.

Two effective high intensity workouts you could consider for off-season are the 4×8 long interval and the 30/15 short interval.

Take-aways

Keen cyclists could potentially improve their upcoming season by keeping the following take-aways in mind:

1 | One high intensity interval every 7-10 days seems to maintain capacity and performance during off-season

2 | Several studies suggest that intensity work is key in preventing de-training during periods with reduced training load

3 | Riders who prevent de-training in off-season can probably start developing their endurance capacity straight off the bat come pre-season, as opposed to spending weeks and months catching up to past levels of performance

4 | There is compelling evidence that preventing de-training during off-season is vital in setting yourself up for the best possible performance next year

Never miss a post – join my newsletter

When you subscribe to my newsletter you will receive science reviews, workout instructions and discussions of best training practices. There is also occasional information about my paid services. I will take care not to clutter your inbox.

References:

- Rønnestad et al. HIT maintains performance during the transition period and improves next season performance in well-trained cyclists. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 2014;114:1831-1839

- Mujika I et al. Effects of training on performance in competitive swimming. Canadian Journal of applied Physiology, 1995;20(4):395-406

- Taylor M, Almquist NW et al. The inclusion of sprints in low-intensity sessions during the transition period of elite cyclists improves endurance performance 6 weeks into the subsequent preparatory period. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2021;16:1502-1509