How much power is required to produce a top result for U17 riders? And what is it that separates successful riders from their less competitive peers?

These are questions of interest for ambitious young cyclists and their coaches alike.

The requirements of elite senior racing are fairly well described through test results of elite cyclists and reviews of race data (1-5).

By comparison, we know less about what is required to succeed as a U17 category rider.

A recent study out of the University of Milan provides new insight into this question (6).

Featured image credit: Radu Razvan/Shutterstock.com

What did they study?

Gallo and colleagues asked the question whether power profile, body type or maturity influence race results in U17 cyclists.

They then examined power profiles and bodily characteristics in 103 male road cyclists over a 10 year period.

The riders who partook were 15-16 years of age and were all members of 4 different Italian cycling teams.

All participants undertook in-season recording of height, weight, BMI, power at 2 mmol/L and 4 mmol/L lactate. In addition, the authors calculated their peak height velocity, which is considered a measure of biological maturity.

Based on racing results, riders were characterised as either “successful” or “unsuccessful”. To be labled “successful”, riders had to achieve at least one top-5 finish in a race throughout the season.

The authors then compared the recordings of the successful and unsuccessful riders.

What did they find?

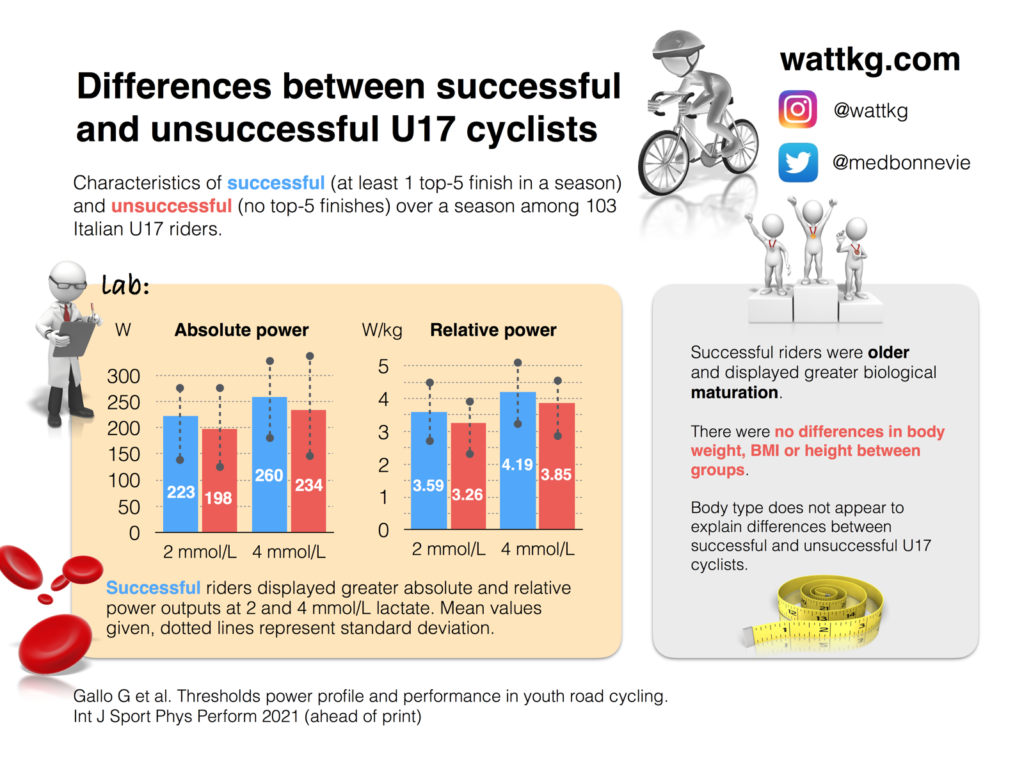

Results revealed that successful riders were older and displayed significantly greater power outputs at 2 and 4 mmol/L lactate compared to unsuccessful riders.

Greater power in successful riders

At an intensity of 2 mmol/L lactate, which is typically the borderline between low and moderate intensity work, successful riders produced a mean power of 223 W (standard deviation ranged 135-285 W) versus 198 W (125-288 W) in unsuccessful riders.

Relative power at 2 mmol/L was also higher in the successful group. They achieved a mean of 3.59 W/kg versus 3.26 W/kg in the unsuccessful group.

Power at 4 mmol/L lactate is usually considered a rough approximation of anaerobic threshold power, although individual variation may deviate considerably. At 4 mmol/L, successful riders produced a mean of 260 W (182-327 W). This was higher than the 234 W (147-342) of unsuccessful riders.

At 4 mmol/L lactate, relative power too was higher with 4.19 W/kg in successful riders versus 3.85 W/kg in the unsuccessful group.

As a side note, we can see that the successful riders are already well on their way to achieve the critical power demonstrated by U23 riders.

No difference in body types

Interestingly, there was no significant difference in height, weight or BMI between successful and unsuccessful riders.

However, there was a difference in age.

As you may expect, older riders appeared to perform better than the younger ones. Similarly, there was a greater degree of developmental maturity in the successful group compared to the unsuccessful one.

“Successful cyclists were also older and with advanced biological maturation than their unsuccessful counterparts, although no differences in anthropometric characteristics were highlighted. This finding could suggest that success in youth categories is highly dependent on the level of maturation of the athletes, although biological age was only theoretically derived.”

– Gallo et al. Int Journ Sport Phys Perform 2021

No training data

Unfortunately, this study did not collect training data from the riders.

As such, we cannot say wether the successful riders were stronger due to greater biological age, better genes or if they were also better trained.

Athletic maturity, that is the condition of anatomy and physiology achieved through years of training, may differ considerably between riders of similar age.

Therefore, it would have been interesting to know how many years the riders had trained for.

The type of rider who would come out short-handed in these comparisons would be someone that is fairly new to the sport of cycling (low athletic maturity) in combination with being behind in physical growth.

This type of rider may, with persistent training, experience great progress over the next few years as both their athletic maturity and physical growth catches up.

Practical application: training for a successful career

In summary, the Gallo study showed that successful riders were older, displayed greater biological maturity and recorded higher power outputs at 2 and 4 mmol/L.

So what does this mean to young and ambitious riders and their coaches?

Here are a few pointers (and I emphasise, these are thoughts of my own).

1. Target power values

At the very least, these results provide a benchmark as to what absolute and relative power outputs are likely to produce top-5 finishes.

The relative power outputs in particular may serve as yardsticks to pursue for ambitious riders.

2. Don’t sweat over body type

This study clearly showed that when considered at group level, successful and unsuccessful riders did not differ in body type when measured by hight, weight or BMI.

In my opinion, adolescence is such an important period for establishing healthy habits and developing a solid training base to endure the future training loads required for pursuit of success at junior and senior level.

The findings of Gallo and colleagues should serve as reassurement to athletes and coaches to first and foremost focus on ensuring a strong and healthy physiological development.

This is NOT the time to get tangled up in the many tripwires associated with pursuit of weight loss (even the pros mess this up, despite having professional support).

3. Don’t go in the quick-fix trap

With these benchmark power values as reference, it may be tempting to try pursue these numbers as quickly as possible.

This may easily lead down a path of overly optimistic doses of threshold and/or VO2 max training. In my experience, low intensity training of good quality tends to suffer in such instances.

Keep in mind that volumes of low intensity work is probably required to achieve strong adaptation to your interval training, as well as for developing metabolic flexibility and load tolerance (7-9).

Low intensity, longer duration training is effective in stimulating physiological adaptations and should not be viewed as wasted training time.

– Seiler & Tønnessen, Sportscience 2009

Aside from performing in the up-coming season, one of the most important tasks for aspiring future pro riders is to develop a strong training base through progressive volume increases – in order to prepare for the big amounts of training required at an elite adult level.

While loads of intensive interval training may work well short-term, you may struggle to achieve the required training volumes in later years if you skip your low intensity endurance rides (my personal experience and opinion).

An established endurance base built from high volumes of training may be an important precondition for tolerating and responding well to a substantial increase in training intensity over the short term (10).

– Stephen Seiler, Int J Sports Phys Perform 2010

Solid amounts of proper low intensity training is money in the bank to be withdrawn in later years. Without it, you will probably struggle when pursuing the higher levels of elite performance.

4. You still got time

If you are a 14-15 year old rider, and you still are not performing at the high level you desire – know that you still got time.

For starters, chances are that those riders who are currently stronger than you are either older, more biologically mature or have more years of training experience than you.

Recent work by Mostaert and colleagues report that older cyclists have an advantage at U15 level, and that this effect is smaller in U17 before vanishing at U19 level (11).

In other words, the impact of age diminishes towards the end of the teenage years.

This study also made another interesting discovery.

The authors report that success rate at U15 level does not predict success at adult age. Whereas at U17 level, top-10 finishes start becoming predictive of success in adult age. At U19 level, this relationship between performance and senior success is even stronger.

So, do not worry if you’re not at the front of the pack at 14 or 15.

Know that your physiology will probably catch up with those riders that are older and/or more early developers.

Do what you can develop a strong training base in order to allow yourself to adapt to progressively bigger training loads each year. Put sufficient “money in the bank” and aim to withdraw it with interest, as you enter U17 and even more so U19.

Meanwhile, gather as much experience from training and racing as you can the upcoming years. And don’t sweat it if you’re a bit behind the biggest guys or girls.

And last, but not least – don’t forget to have fun along the way!

Best of luck with your training.

– Martin

References:

- Sanders D et al. Intensity and load characteristics of professional road cycling: differences between men’s and women’s races. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2019;14(3):296-302

- Sanders D et al. The physical demands and power profile of professional men’s cycling races: An updated review. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2020;16(1):3-12

- Menaspà P. Analysis of road sprint cycling performance. Edith Cowan University, 2015

- Bell PG et al. The physiological profile of a multiple Tour de France winning cyclist. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 2017;49(1):115-123

- Pinot J and Grappe F. A six-year monitoring case study of a top-10 cycling Grand Tour finisher. Journal of Sports Sciences, 2015;33(9):907-914

- Gallo G et al. Thresholds power profiles and performance in youth road cycling. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2021 (ahead of print)

- Burton HM et al. Background inactivity blunts metabolic adaptations to intense short-term training. Medicine and Science in sports and Exercise, 2021 (ahead of print)

- Purdom T et al. Understanding the factors that effect maximal fa oxidation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 2018;15(3)

- Seiler S & Tønnessen E. Intervals, thresholds, and long slow distance: The role of intensity and duration in endurance training. Sportscience, 2009;13:32-53

- Seiler S. What is best practice for training intensity and duration distribution in endurance athletes? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2010;5:276-291

- Mostaert M et al. The importance of performance in youth competitions as an indicator of future success in cycling. European Journal of Sport Science, 2021 (ahead of print)